In addition to continued infrastructure development at Starbase, Texas, where SpaceX is headquartered, SpaceX is expanding its Starship operations in Florida, bringing Starship production and launch capabilities to the Space Coast. As flight testing and development of Starship continues at Starbase in Texas, SpaceX is building a new integration facility, called Gigabay, next to its HangarX location at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. Additionally, SpaceX plans to complete the Starship launch pad at Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A) at Kennedy Space Center this year while the Environmental Impact Statements continue for potential Starship flight operations from both LC-39A and Space Launch Complex 37 (SLC-37) at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station (CCSFS).

Expansion of Starship production and launch operations in Florida will enable SpaceX to significantly increase the build and flight rates for Starship, which will be the first rapidly and fully reusable launch vehicle in history. Access to space is a critical and growing need for U.S. national security, leadership in science, the country’s exploration goals, and for the growth of the economy. Starship will ultimately be responsible for sending millions of tons of payload to Mars – building a self-sustaining city to make humanity multiplanetary.

GIGABAY

The Gigabay in Florida will stand 380 feet tall and provide approximately 46.5 million cubic feet of interior processing space with 815,000 square feet of workspace, including ground level, elevated platform work areas, and a work and meeting space on the top floor. Gigabay will be able to support Starship and Super Heavy vehicles up to 81 meters (266 feet) tall and will provide 24 work cells for integration and refurbishment work, along with cranes capable of lifting up to 400 US tons. Compared to the Megabay facilities in Starbase, currently SpaceX’s largest stacking and integration buildings, Gigabay provides more than 11 times the square-footage for workspace, 19 additional work cells, and more than twice the crane lifting capacity.

Site preparations for Gigabay in Florida have already begun, with construction targeted to be complete and the facility operational by the end of 2026. At the same time, we are also building another Gigabay at Starbase in Texas, next to our Starship Starfactory manufacturing facility. Work on this Gigabay has already begun, and the facility is targeted for completion by the end of 2026.

As we work to complete the Gigabay in Florida, we are also designing and planning for a co-located manufacturing facility, similar to the Starfactory in Texas, to enable production of Starships in Florida. To enable initial Starship flights from Florida while our Space Coast Starship manufacturing, integration, and refurbishment facilities are being completed, we will first transport completed Super Heavy boosters and Starship upper stage ships from Starbase via barge to build up a Starship fleet in Florida. With production, integration, refurbishment, and launch facilities in Florida as well as Texas, we will be in a position to quickly ramp Starship’s launch rate via rapid reusability.

STARSHIP AT THE SPACE COAST

To support initial Starship launches from Florida, SpaceX is building a Starship launch and catch site at LC-39A at Kennedy Space Center. This Starship pad at LC-39A will include learnings from Starship’s first two pads in Starbase. In 2022, we stacked the launch tower at LC-39A. In the coming months, teams will build and install the pad’s deflector system, which provides cooling and sound suppression water during Starship launches and catches. This new deflector will be nearly identical to the one being installed to support the second launch pad at Starbase. Pending completion of environmental reviews, SpaceX intends to conduct Starship's first Florida launch from LC-39A in late 2025.

To support the needed Starship flight rate to make humanity a multiplanetary civilization, which involves not only the launch of cargo and people but also the propellant tankers to enable on-orbit refueling, SpaceX is also interested in enabling Starship launches from SLC-37 at CCSFS. SpaceX has been given a limited Right of Entry for SLC-37 in support of conducting further due diligence of the site in order to move forward with the Environmental Impact Study (EIS), led by the Department of the Air Force, for Starship and Super Heavy Operations at CCSFS. SLC-37 was built in the late 1950s and early 1960s. NASA used the pad from 1964 to 1968 for testing of the Saturn I and Saturn IB rockets as part of the Apollo program. From 2002 to 2024, the pad was used for the Delta IV rocket.

The seventh flight test of Starship and Super Heavy flew with ambitious goals, aiming to successfully repeat the core capability of returning and catching a booster while launching an upgraded design of the upper stage. While not every test objective was completed, the lessons learned will roll directly into future vehicles to make them more capable as Starship advances toward full and rapid reuse.

On January 16, 2025, Starship successfully lifted off at 4:37 p.m. CT from Starbase in Texas. At launch, all 33 Raptor engines on the Super Heavy booster started up successfully and completed a full duration burn during ascent. After powering down all but the three center engines on Super Heavy, Starship ignited all six of its Raptor engines to separate in a hot-staging maneuver and continue its ascent to space.

Following stage separation, Super Heavy initiated its boostback burn to propel the rocket toward its intended landing location. It successfully lit 12 of the 13 engines commanded to start, with a single Raptor on the middle ring safely aborting on startup due to a low-power condition in the igniter system. Raptor engines on upcoming flights have a pre-planned igniter upgrade to mitigate this issue. The boostback burn was completed successfully and sent Super Heavy back to the launch site for catch.

The booster successfully relit all 13 planned middle ring and center Raptor engines for its landing burn, including the engine that did not relight for boostback burn. The landing burn slowed the booster down and maneuvered it to the launch and catch tower arms at Starbase, resulting in the second ever successful catch of Super Heavy.

After vehicle separation, Starship's six second stage Raptor engines powered the vehicle along its expected trajectory. Approximately two minutes into its burn, a flash was observed in the aft section of the vehicle near one of the Raptor vacuum engines. This aft section, commonly referred to as the attic, is an unpressurized area between the bottom of the liquid oxygen tank and the aft heatshield. Sensors in the attic detected a pressure rise indicative of a leak after the flash was seen.

Roughly two minutes later, another flash was observed followed by sustained fires in the attic. These eventually caused all but one of Starship’s engines to execute controlled shut down sequences and ultimately led to a loss of communication with the ship. Telemetry from the vehicle was last received just over eight minutes and 20 seconds into flight.

Contact with Starship was lost prior to triggering any destruct rules for its Autonomous Flight Safety System, which was fully healthy when communication was lost. The vehicle was observed to break apart approximately three minutes after loss of contact during descent. Post-flight analysis indicates that the safety system did trigger autonomously, and breakup occurred within Flight Termination System expectations.

The most probable root cause for the loss of ship was identified as a harmonic response several times stronger in flight than had been seen during testing, which led to increased stress on hardware in the propulsion system. The subsequent propellant leaks exceeded the venting capability of the ship’s attic area and resulted in sustained fires.

Immediately following the anomaly, the pre-coordinated response plan developed by SpaceX, the FAA, and ATO (air traffic control) went into effect. All debris came down within the pre-planned Debris Response Area, and there were no hazardous materials present in the debris and no significant impacts expected to occur to marine species or water quality. SpaceX reached out immediately to the government of Turks and Caicos and worked with them and the United Kingdom to coordinate recovery and cleanup efforts. While an early end to the flight test is never a desired outcome, the measures put in place ahead of launch demonstrated their ability to keep the public safe.

SpaceX led the investigation efforts with oversight from the FAA and participation from NASA, the National Transportation Safety Board, and the U.S. Space Force. SpaceX is working with the FAA to either close the mishap investigation or receive a flight safety determination, along with working on a license authorization to enable its next flight of Starship.

As part of the investigation, an extended duration static fire was completed with the Starship flying on the eighth flight test. The 60-second firing was used to test multiple engine thrust levels and three separate hardware configurations in the Raptor vacuum engine feedlines to recreate and address the harmonic response seen during Flight 7. Findings from the static fire informed hardware changes to the fuel feedlines to vacuum engines, adjustments to propellant temperatures, and a new operating thrust target that will be used on the upcoming flight test.

To address flammability potential in the attic section on Starship, additional vents and a new purge system utilizing gaseous nitrogen are being added to the current generation of ships to make the area more robust to propellant leakage. Future upgrades to Starship will introduce the Raptor 3 engine, reducing the attic volume and eliminating the majority of joints that can leak into this volume.

Starship’s seventh flight test was a reminder that developmental progress is not always linear, and putting flight hardware in a flight environment is the fastest way to demonstrate how thousands of distinct parts come together to reach space. Upcoming flights will continue to target ambitious goals in the pursuit of full and rapid reusability.

SpaceX was founded in 2002 to expand access to outer space. Not just for government or traditional satellite operators, but for new participants around the globe. Today, we’re flying at an unprecedented pace as the world’s most active launch services provider. SpaceX is safely and reliably launching astronauts, satellites, and other payloads on missions benefiting life on Earth and preparing humanity for our ultimate goal: to explore other planets in our solar system and beyond.

Starship is paramount to making that sci-fi future, along with a growing number of U.S. national priorities, a reality. It is the largest and most powerful space transportation system ever developed, and its fully and rapidly reusable design will exponentially increase humanity’s ability to access and utilize outer space. Full reusability has been an elusive goal throughout the history of spaceflight, piling innumerable technical challenges on what is already the most difficult engineering pursuit in human existence. It is rocket science, on ludicrous mode.

Every flight of Starship has made tremendous progress and accomplished increasingly difficult test objectives, making the entire system more capable and more reliable. Our approach of putting flight hardware in the flight environment as often as possible maximizes the pace at which we can learn recursively and operationalize the system. This is the same approach that unlocked reuse on our Falcon fleet of rockets and made SpaceX the leading launch provider in the world today.

To do this and do it rapidly enough to meet commitments to national priorities like NASA’s Artemis program, Starships need to fly. The more we fly safely, the faster we learn; the faster we learn, the sooner we realize full and rapid rocket reuse. Unfortunately, we continue to be stuck in a reality where it takes longer to do the government paperwork to license a rocket launch than it does to design and build the actual hardware. This should never happen and directly threatens America’s position as the leader in space.

FLIGHT 5

The Starship and Super Heavy vehicles for Flight 5 have been ready to launch since the first week of August. The flight test will include our most ambitious objective yet: attempt to return the Super Heavy booster to the launch site and catch it in mid-air.

This will be a singularly novel operation in the history of rocketry. SpaceX engineers have spent years preparing and months testing for the booster catch attempt, with technicians pouring tens of thousands of hours into building the infrastructure to maximize our chances for success. Every test comes with risk, especially those seeking to do something for the first time. SpaceX goes to the maximum extent possible on every flight to ensure that while we are accepting risk to our own hardware, we accept no compromises when it comes to ensuring public safety.

It's understandable that such a unique operation would require additional time to analyze from a licensing perspective. Unfortunately, instead of focusing resources on critical safety analysis and collaborating on rational safeguards to protect both the public and the environment, the licensing process has been repeatedly derailed by issues ranging from the frivolous to the patently absurd. At times, these roadblocks have been driven by false and misleading reporting, built on bad-faith hysterics from online detractors or special interest groups who have presented poorly constructed science as fact.

We recently received a launch license date estimate of late November from the FAA, the government agency responsible for licensing Starship flight tests. This is a more than two-month delay to the previously communicated date of mid-September. This delay was not based on a new safety concern, but instead driven by superfluous environmental analysis. The four open environmental issues are illustrative of the difficulties launch companies face in the current regulatory environment for launch and reentry licensing.

STEEL AND WATER

Starship’s water-cooled steel flame deflector has been the target of false reporting, wrongly alleging that it pollutes the environment or has operated completely independent of regulation. This narrative omits fundamental facts that have either been ignored or intentionally misinterpreted.

At no time did SpaceX operate the deflector without a permit. SpaceX was operating in good faith under a Multi-Sector General Permit to cover deluge operations under the supervision of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). SpaceX worked closely with TCEQ to incorporate numerous mitigation measures prior to its use, including the installation of retention basins, construction of protective curbing, plugging of outfalls during operations, and use of only potable (drinking) water that does not come into contact with any industrial processes. A permit number was assigned and made active in July 2023. TCEQ officials were physically present at the first testing of the deluge system and given the opportunity to observe operations around launch.

The water-cooled steel flame deflector does not spray pollutants into the surrounding environment. Again, it uses literal drinking water. Outflow water has been sampled after every use of the system and consistently shows negligible traces of any contaminants, and specifically, that all levels have remained below standards for all state permits that would authorize discharge. TCEQ, the FAA, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service evaluated the use of the system prior to its initial use, and during tests and launch, and determined it would not cause environmental harm.

When the EPA issued its Administrative Order in March 2024, it was done before seeking a basic understanding of the facts of the water-cooled steel flame deflector’s operation or acknowledgement that we were operating under the Texas Multi-Sector General Permit. After meeting with the EPA—during which the EPA stated their intent was not to stop testing, preparation, or launch operations—it was decided that SpaceX should apply for an individual discharge permit. Despite our previous permitting, which was done in coordination with TCEQ, and our operation having little to nothing in common with industrial waste discharges covered by individual permits, we applied for an individual permit in July 2024.

The subsequent fines levied on SpaceX by TCEQ and the EPA are entirely tied to disagreements over paperwork. We chose to settle so that we can focus our energy on completing the missions and commitments that we have made to the U.S. government, commercial customers, and ourselves. Paying fines is extremely disappointing when we fundamentally disagree with the allegations, and we are supported by the fact that EPA has agreed that nothing about the operation of our flame deflector will need to change. Only the name of the permit has changed.

GOOD STEWARD

No launch site operates in a vacuum. As we have built up capacity to launch and developed new sites across the country, we have always been committed to public safety and mitigating impacts to the environment. At Starbase, we implement an extensive list of mitigations developed with federal and state agencies, many of which require year-round monitoring and frequent updates to regulators and consultation with independent biological experts. The list of measures we take just for operations in Texas is over two hundred items long, including constant monitoring and sampling of the short and long-term health of local flora and fauna. The narrative that we operate free of, or in defiance of, environmental regulation is demonstrably false.

Environmental regulations and mitigations serve a noble purpose, stemming from common-sense safeguards to enable progress while preventing undue impact to the environment. However, with the licensing process being drawn out for Flight 5, we find ourselves delayed for unreasonable and exasperating reasons.

On Starship’s fourth flight, the top of the Super Heavy booster, commonly known as the hot-stage, was jettisoned to splash down on its own in the Gulf of Mexico. The hot-stage plays an important part in protecting the booster during separation from Starship’s upper stage before detaching during the booster’s return flight. This operation was analyzed thoroughly ahead of Starship’s fourth flight, specifically focused on any potential impact to protected marine species. Given the distribution of marine animals in the specific landing area and comparatively small size of the hot-stage, the probability of a direct impact is essentially zero. This is something previously determined as standard practice by the FAA and the National Marine Fisheries Service for the launch industry at large, which disposes of rocket stages and other hardware in the ocean on every single launch, except of course, for our own Falcon rockets which land and are reused. The only proposed modification for Starship’s fifth flight is a marginal change in the splashdown location of the hot-stage which produces no increase in likelihood for impacting marine life. Despite this, the FAA leadership approved a 60-day consultation with the National Marine Fisheries Service. Furthermore, the mechanics of these types of consultations outline that any new questions raised during that time can reset the 60-day counter, over and over again. This single issue, which was already exhaustively analyzed, could indefinitely delay launch without addressing any plausible impact to the environment.

Another unique aspect to Starship’s fifth flight and a future return and catch of the Super Heavy booster will be the audible sonic booms in the area around the return location. As we’ve previously noted, the general impact to those in the surrounding area of a sonic boom is the brief thunder-like noise. The FAA, in consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, evaluated sonic booms from the landing of the Super Heavy and found no significant impacts to the environment. Although animals exposed to the sonic booms may be briefly startled, numerous prior studies have shown sonic booms of varying intensity have no detrimental effect on wildlife. Despite this documented evidence, the FAA leadership approved an additional 60-day consultation with U.S. Fish and Wildlife as a slightly larger area could experience a sonic boom.

Lastly, the area around Starbase is well known as being host to various protected birds. SpaceX already has extensive mitigations in place and has been conducting biological monitoring for birds near Starbase for nearly 10 years. The protocol for the monitoring was developed with U.S. Fish and Wildlife service, and is conducted by professional, qualified, independent biologists. To date, the monitoring has not shown any population-level impacts to monitored bird populations, despite unsubstantiated claims to the contrary that the authors themselves later amended. Even though Starship’s fifth flight will take place outside of nesting season, SpaceX is still implementing additional mitigations and monitoring to minimize impacts to wildlife, including infrared drone surveillance pre- and post-launch to track nesting presence. We are also working with USFWS experts to assess deploying special protection measures prior to launches during bird nesting season.

SpaceX is committed to minimizing impact and enhancing the surrounding environment where possible. One of our proudest partnerships in South Texas is with Sea Turtle Inc, a local nonprofit dedicated to sea turtle conservation. SpaceX assists with finding and transporting injured sea turtles to their facilities for treatment. SpaceX has also officially adopted Boca Chica Beach through the Texas General Lands Office Adopt a Beach Program, with the responsibility of picking up litter and promoting a litter-free environment. SpaceX sponsors and participates in quarterly beach cleanups as well as quarterly State Highway 4 cleanups. SpaceX has removed hundreds of pounds of trash from the beach and State Highway 4 over the last several years. SpaceX also fosters environmental education at the local level by hosting school tours as well as an Annual Environmental Education Day with Texas Parks and Wildlife, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, and Sea Turtle Inc.

TO FLY

Despite a small, but vocal, minority of detractors trying to game the regulatory system to obstruct and delay the development of Starship, SpaceX remains committed to the mission at hand. Our thousands of employees work tirelessly because they believe that unlimited opportunities and tangible benefits for life on Earth are within reach if humanity can fundamentally advance its ability to access space. This is why we’re committed to continually pushing the boundaries of spaceflight, with a relentless focus on safety and reliability.

Because life will be multiplanetary, and will be made possible by the farsighted strides we take today.

In the past four years, SpaceX has launched thirteen human spaceflight missions, safely flying 50 crewmembers to and from Earth’s orbit and creating new opportunities for humanity to live, work, and explore what is possible in space. Dragon’s 46 missions overall to orbit have delivered critical supplies, scientific research, and astronauts to the International Space Station, while also opening the door for commercial astronauts to explore Earth’s orbit.

As early as this year, Falcon 9 will launch Dragon’s sixth commercial astronaut mission, Fram2, which will be the first human spaceflight mission to explore Earth from a polar orbit and fly over the Earth’s polar regions for the first time. Named in honor of the ship that helped explorers first reach Earth’s Arctic and Antarctic regions, Fram2 will be commanded by Chun Wang, an entrepreneur and adventurer from Malta. Wang aims to use the mission to highlight the crew’s explorational spirit, bring a sense of wonder and curiosity to the larger public, and highlight how technology can help push the boundaries of exploration of Earth and through the mission’s research.

Joining Wang on the mission is a crew of international adventurers: Norway’s Jannicke Mikkelsen, vehicle commander; Australia’s Eric Philips, vehicle pilot; and Germany’s Rabea Rogge, mission specialist. This will be the first spaceflight for each of the crewmembers.

Throughout the 3-to-5-day mission, the crew plans to observe Earth’s polar regions through Dragon’s cupola at an altitude of 425 – 450 km, leveraging insight from space physicists and citizen scientists to study unusual light emissions resembling auroras. The crew will study green fragments and mauve ribbons of continuous emissions comparable to the phenomenon known as STEVE (Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement), which has been measured at an altitude of approximately 400 - 500 km above Earth’s atmosphere. The crew will also work with SpaceX to conduct a variety of research to better understand the effects of spaceflight on the human body, which includes capturing the first human x-ray images in space, Just-in-Time training tools, and studying the effects of spaceflight on behavioral health, all of which will help in the development of tools needed to prepare humanity for future long-duration spaceflight.

Falcon 9 will launch Fram2 to a polar orbit from Florida no earlier than late 2024.

With each flight of Starship and the Super Heavy booster, we get closer to our goal of making life multiplanetary. The most important advancement to make this happen is full and rapid reusability of the entire launch system, operating Starship like an airplane which is fully and rapidly reusable after each flight. To do this, we have designed Starship’s upper stage and the Super Heavy booster to be capable of returning to the launch site. The returning vehicles will slow down from supersonic speeds, resulting in audible sonic booms in the area around the return location.

A sonic boom is a brief, thunder-like noise a person on the ground hears when an aircraft or other object travels faster than the speed of sound. As a fast-moving object travels through the air, it pushes the air aside and creates a wave of pressure which eventually reaches the ground. The change in air pressure associated with a sonic boom, known as overpressure, increases only a few pounds per square foot. A person could experience a similar pressure change by riding down several floors in an elevator. What makes sonic booms audible is the quick speeds at which the pressure change occurs.

Generally, the only impact to those in the surrounding area of a sonic boom is the brief noise. There are many variables that determine the impact of sonic booms, including the mass, shape and size of the object traveling at high speeds, along with its altitude and flight path. External factors like weather conditions can also affect the intensity of a sonic boom. The strongest effects of the sonic boom’s pressure change are localized to the area directly beneath the vehicle, concentrated under the rocket’s flight path and the landing site.

Sonic booms in spaceflight have typically only been experienced by observers on Earth when encountering vehicles designed to be reused, such as SpaceX’s Falcon family of rockets. When the first stage booster of a Falcon rocket returns for landing, its size and speed generate multiple sonic booms heard on the ground as a double clap of thunder. Similar sonic booms were heard during the return and landing of the NASA’s space shuttle. In each case, the sonic boom marks the end of just one in a series of missions for the vehicle returning from flight.

Data gathered from the first ever Super Heavy landing burn and splashdown on Starship’s fourth flight test indicates that while Super Heavy’s sonic boom will be more powerful than those generated by Falcon landings, it does not pose any risk of injury to those in the surrounding areas. The strongest effects will be localized to the area immediately around the Starbase launch pad. This area is cleared well in advance of launch and has been rigorously designed to withstand the environments of launching and returning the most powerful rocket ever flown.

Sonic booms announce the return of rockets and spacecraft built to be reused. With Starship, they’ll signal the arrival of a rapidly reusable future in spaceflight to travel to Earth orbit, the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft is designed to fly both astronauts and cargo to and from Earth’s orbit, advancing humanity’s ability to live and work in space on the road to making life multiplanetary.

In June 2010, Dragon became the first privately-developed spacecraft in history to launch, orbit Earth, reenter, and be recovered back on Earth. This milestone was followed by Dragon becoming the first commercial vehicle to visit the International Space Station in May 2012 under NASA’s Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program – an incredibly successful public-private partnership that has led to regular commercial cargo resupply missions to the space station through NASA’s Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contract. In 2020, NASA certified Dragon for human spaceflight after the historic launch of NASA astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken to the space station.

Dragon’s now 45 missions to orbit have helped ensure the continued operation of the space station – delivering critical supplies, scientific research, and astronauts to the orbiting laboratory – while also creating greater opportunities for humanity to explore Earth’s orbit.

Dragon Design and Current Recovery Operations

The Dragon spacecraft is comprised of two parts: a pressurized section that safely flies crew and cargo, and an unpressurized expendable section called the trunk, which contains hardware used for spacecraft power and cooling while on-orbit. On cargo missions, the trunk can also deliver or dispose of unpressurized hardware from the International Space Station, depending on mission needs. When Dragon returns to Earth, the trunk is jettisoned prior to the spacecraft safely splashing down.

During Dragon’s first 21 missions, the trunk remained attached to the vehicle’s pressurized section until after the deorbit burn was completed. Shortly before the spacecraft began reentering the atmosphere, the trunk was jettisoned to ensure it safely splashed down in unpopulated areas in the Pacific Ocean.

After seven years of successful recovery operations on the U.S. West Coast, Dragon recovery operations moved to the East Coast in 2019, enabling teams to unpack and deliver critical cargo to NASA teams in Florida more efficiently and transport crews more quickly to Kennedy Space Center. Additionally, the proximity of the new splashdown locations to SpaceX’s Dragon processing facility at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida allowed SpaceX teams to recover and refurbish Dragon spacecraft at a faster rate to support a rapidly growing Dragon manifest after the completion of NASA’s Demo-2 mission in August 2020.

This shift required SpaceX to develop what has become our current Dragon recovery operations, first implemented during the Demo-1 and CRS-21 missions. Today, Dragon’s trunk is jettisoned prior to the vehicle’s deorbit burn while still in orbit, passively reentering and breaking up in the Earth’s atmosphere in the days to months that follow. As the trunk does not have any maneuvering capabilities of its own after separation, the location and precise timing of the trunk’s reentry cannot be predicted and is dependent upon solar activity.

When developing Dragon’s current reentry operations, SpaceX and NASA engineering teams used industry-standard models to understand the trunk’s breakup characteristics. These models predicted that the trunk would fully burn up due to the high temperatures created by air resistance during high-speed reentries into Earth’s atmosphere, leaving no debris. The results of these models was a determining factor in our decision to passively deorbit the trunk and enable Dragon splashdowns off the coast of Florida.

In 2022, however, trunk debris from NASA’s Crew-1 mission to the International Space Station was discovered in Australia, indicating the industry models were not fully accurate with regards to large, composite structures such as Dragon’s trunk. SpaceX and NASA reviewed the data and performed additional materials testing to better understand the trunk’s break-up characteristics and improve the respective modeling.

To date, the majority of trunk debris has reentered over unpopulated ocean areas. In the last six months, however, SpaceX became aware of three new cases where trunk debris was found on land; SpaceX is unaware of any structure damage or injuries caused by these debris.

Looking Ahead

SpaceX is committed to safe spaceflight operations and public safety; it is at the core of SpaceX’s operations. After drawing new conclusions based on the data, we made two immediate changes while continuing to find a longer-term solution. First, in agreement with NASA, we paused trunk payload disposal during return operations; an empty trunk has a higher probability of fully burning up during reentry than one with payloads. Next, SpaceX implemented material changes to certain components of Dragon’s trunk to further improve the probability of it burning up during reentry.

Simultaneously, SpaceX engineering teams explored a wide variety of solutions to fully eliminate the risk of trunk debris landing on populated areas without increasing risk to Dragon crew or the public. Some of the options studied included a complete trunk redesign; a dedicated propulsion and guidance system to allow the trunk to deorbit itself; jettisoning the trunk at different times in the deorbit burn; and more.

After careful review and consideration of all potential solutions – coupled with the new knowledge about the standard industry models and that Dragon trunks do not fully burn-up during reentry – SpaceX teams concluded the most effective path forward is to return to West Coast recovery operations.

To accomplish this, SpaceX will implement a software change that will have Dragon execute its deorbit burn before jettisoning the trunk, similar to our first 21 Dragon recoveries. Moving trunk separation after the deorbit burn places the trunk on a known reentry trajectory, with the trunk safely splashing down uprange of the Dragon spacecraft off the coast of California. SpaceX is working with NASA, the FAA, and other federal agencies to evaluate and assess all potential return locations off the coast of California to ensure safe and reliable Dragon splashdowns on the West Coast.

To support these changes, a Dragon recovery vessel will move to the Pacific, where we will utilize existing SpaceX facilities in the Port of Long Beach to support initial post-flight work and operations on Dragon. Post-splashdown, crew and cargo will transit to California ahead of their final destinations, such as Houston, Texas or Cape Canaveral, Florida. Dragon refurbishment will continue to primarily take place at our Dragon processing facility at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida to prepare the Dragon spacecraft for its next flight.

Continued innovation of spacecraft design and operations is critical to ensure Dragon continues to safely fly to and from Earth’s orbit. This new path will help make this possible while also keeping the public safe as we work toward becoming a spacefaring civilization.

SpaceX submitted its mishap report to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regarding Falcon 9’s launch anomaly on July 11, 2024. SpaceX’s investigation team, with oversight from the FAA, was able to identify the most probable cause of the mishap and associated corrective actions to ensure the success of future missions.

Post-flight data reviews confirmed Falcon 9’s first stage booster performed nominally through ascent, stage separation, and a successful droneship landing. During the first burn of Falcon 9’s second stage engine, a liquid oxygen leak developed within the insulation around the upper stage engine. The cause of the leak was identified as a crack in a sense line for a pressure sensor attached to the vehicle’s oxygen system. This line cracked due to fatigue caused by high loading from engine vibration and looseness in the clamp that normally constrains the line. Despite the leak, the second stage engine continued to operate through the duration of its first burn, and completed its engine shutdown, where it entered the coast phase of the mission in the intended elliptical parking orbit.

A second burn of the upper stage engine was planned to circularize the orbit ahead of satellite deployment. However, the liquid oxygen leak on the upper stage led to the excessive cooling of engine components, most importantly those associated with delivery of ignition fluid to the engine. As a result, the engine experienced a hard start rather than a controlled burn, which damaged the engine hardware and caused the upper stage to subsequently lose attitude control. Even so, the second stage continued to operate as designed, deploying the Starlink satellites and successfully completing stage passivation, a process of venting down stored energy on the stage, which occurs at the conclusion of every Falcon mission.

Following deployment, the Starlink team made contact with 10 of the satellites to send early burn commands in an attempt to raise their altitude. Unfortunately, the satellites were in an enormously high-drag environment with a very low perigee of only 135 km above the Earth. As a result, all 20 Starlink satellites from this launch re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere. By design, Starlink satellites fully demise upon reentry, posing no threat to public safety. To-date, no debris has been reported after the successful deorbit of Starlink satellites.

SpaceX engineering teams have performed a comprehensive and thorough review of all SpaceX vehicles and ground systems to ensure we are putting our best foot forward as we return to flight. For near term Falcon launches, the failed sense line and sensor on the second stage engine will be removed. The sensor is not used by the flight safety system and can be covered by alternate sensors already present on the engine. The design change has been tested at SpaceX’s rocket development facility in McGregor, Texas, with enhanced qualification analysis and oversight by the FAA and involvement from the SpaceX investigation team. An additional qualification review, inspection, and scrub of all sense lines and clamps on the active booster fleet led to a proactive replacement in select locations.

Safety and reliability are at the core of SpaceX’s operations. It would not have been possible to achieve our current cadence without this focus, and thanks to the pace we’ve been able to launch, we’re able to gather unprecedented levels of flight data and are poised to rapidly return to flight, safely and with increased reliability. Our missions are of critical importance – safely carrying astronauts, customer payloads, and thousands of Starlink satellites to orbit – and they rely on the Falcon family of rockets being one of the most reliable in the world. We thank the FAA and our customers for their ongoing work and support.

Starship is designed to fundamentally alter humanity’s access to space, ultimately enabling us to make life multiplanetary. The third flight test of Starship and Super Heavy made tremendous strides towards this future and was an important step on the road to rapidly reliable reusable rockets.

On March 14, 2024, Starship successfully lifted off at 8:25 a.m. CT from Starbase, Texas. All 33 Raptor engines on the Super Heavy Booster started up successfully and completed a full-duration burn during ascent, followed by a successful hot-stage separation. This was the second successful ascent of the Super Heavy booster, the world’s most powerful launch vehicle. At stage separation, Starship's six second stage Raptor engines all started successfully and powered the vehicle to its expected trajectory, becoming the first Starship to complete its full-duration ascent burn.

Following stage separation, Super Heavy initiated its boostback burn, which sends commands to 13 of the vehicle’s 33 Raptor engines to propel the rocket toward its intended landing location. All 13 engines ran successfully until six engines began shutting down, triggering a benign early boostback shutdown.

The booster then continued to descend until attempting its landing burn, which commands the same 13 engines used during boostback to perform the planned final slowing for the rocket before a soft touchdown in the water, but the six engines that shut down early in the boostback burn were disabled from attempting the landing burn startup, leaving seven engines commanded to start up with two successfully reaching mainstage ignition. The booster had lower than expected landing burn thrust when contact was lost at approximately 462 meters in altitude over the Gulf of Mexico and just under seven minutes into the mission.

The most likely root cause for the early boostback burn shutdown was determined to be continued filter blockage where liquid oxygen is supplied to the engines, leading to a loss of inlet pressure in engine oxygen turbopumps. SpaceX implemented hardware changes ahead of Flight 3 to mitigate this issue, which resulted in the booster progressing to its first ever landing burn attempt. Super Heavy boosters for Flight 4 and beyond will get additional hardware inside oxygen tanks to further improve propellant filtration capabilities. And utilizing data gathered from Super Heavy’s first ever landing burn attempt, additional hardware and software changes are being implemented to increase startup reliability of the Raptor engines in landing conditions.

During Starship’s coast phase, the vehicle accomplished several of the flight test’s additional objectives, including the first ever test of its payload door in space. The vehicle also successfully completed a propellant transfer demonstration, moving liquid oxygen from a header tank into the main tank. This test provided valuable data for eventual ship-to-ship propellant transfers that will enable missions like returning astronauts to the Moon under NASA’s Artemis program.

Several minutes after Starship began its coast phase, the vehicle began losing the ability to control its attitude. Starship continued flying its nominal trajectory but given the loss of attitude control, the vehicle automatically triggered a pre-planned command to skip its planned on-orbit relight of a single Raptor engine.

Starship went on to experience its first ever reentry from space, providing valuable data on heating and vehicle control during hypersonic reentry. The lack of attitude control resulted in an off-nominal entry, with the ship seeing much larger than anticipated heating on both protected and unprotected areas. High-definition live views of entry and a considerable amount of telemetry were successfully transmitted in real time by Starlink terminals operating on Starship. The flight test’s conclusion came when telemetry was lost at approximately 65 kilometers in altitude, roughly 49 minutes into the mission.

The most likely root cause of the unplanned roll was determined to be clogging of the valves responsible for roll control. SpaceX has since added additional roll control thrusters on upcoming Starships to improve attitude control redundancy and upgraded hardware for improved resilience to blockage.

Following the flight test, SpaceX led the investigation efforts with oversight from the FAA and participation from National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the National Transportation and Safety Board (NTSB). During Flight 3, neither vehicle’s automated flight safety system was triggered, and no vehicle debris impacted outside of pre-defined hazard areas. Pending FAA finding of no public safety impact, a license modification for the next flight can be issued without formal closure of the mishap investigation.

Upgrades derived from the flight test will debut on the next launch from Starbase on Flight 4, as we turn our focus from achieving orbit to demonstrating the ability to return and reuse Starship and Super Heavy. The team incorporated numerous hardware and software improvements in addition to operational changes including the jettison of the Super Heavy’s hot-stage adapter following boostback to reduce booster mass for the final phase of flight.

The third flight of Starship provided a glimpse through brilliant plasma of a rapidly reusable future on the horizon. We’re continuing to rapidly develop Starship, putting flight hardware in a flight environment to learn as quickly as possible as we build a fully reusable transportation system designed to carry crew and cargo to Earth orbit, the Moon, Mars and beyond.

In February 2022, Jared Isaacman and SpaceX announced the Polaris Program, an effort designed to rapidly advance human spaceflight capabilities, while also supporting important causes here on Earth.

Polaris Dawn, the first of the program’s three human spaceflight missions, is targeted to launch to orbit no earlier than summer 2024. During the five-day mission, the crew will perform SpaceX’s first-ever Extravehicular Activity (more commonly known as an EVA or spacewalk) from Dragon, which will also be the first-ever commercial astronaut spacewalk. This historic milestone will also be the first time four astronauts will be exposed to the vacuum of space at the same time.

Supporting the crew throughout the spacewalk will be SpaceX’s newly-developed EVA suit, an evolution of the Intravehicular Activity (IVA) suit crews currently wear aboard Dragon human spaceflight missions. Developed with mobility in mind, SpaceX teams incorporated new materials, fabrication processes, and novel joint designs to provide greater flexibility to astronauts in pressurized scenarios while retaining comfort for unpressurized scenarios. The 3D-printed helmet incorporates a new visor to reduce glare during the EVA in addition to the new Heads-Up Display (HUD) and camera that provide information on the suit’s pressure, temperature, and relative humidity. The suit also incorporates enhancements for reliability and redundancy during a spacewalk, adding seals and pressure valves to help ensure the suit remains pressurized and the crew remains safe.

All of these enhancements to the EVA suit are part of a scalable design, allowing teams to produce and scale to different body types as SpaceX seeks to create greater accessibility to space for all of humanity.

While Polaris Dawn will be the first time the SpaceX EVA suit is used in low-Earth orbit, the suit’s ultimate destiny lies much farther from our home planet. Building a base on the Moon and a city on Mars will require the development of a scalable design for the millions of spacesuits required to help make life multiplanetary.

The goal of SpaceX is to build the technologies necessary to make life multiplanetary. This is the first time in the 4-billion-year history of Earth that it’s possible to realize that goal and protect the light of consciousness.

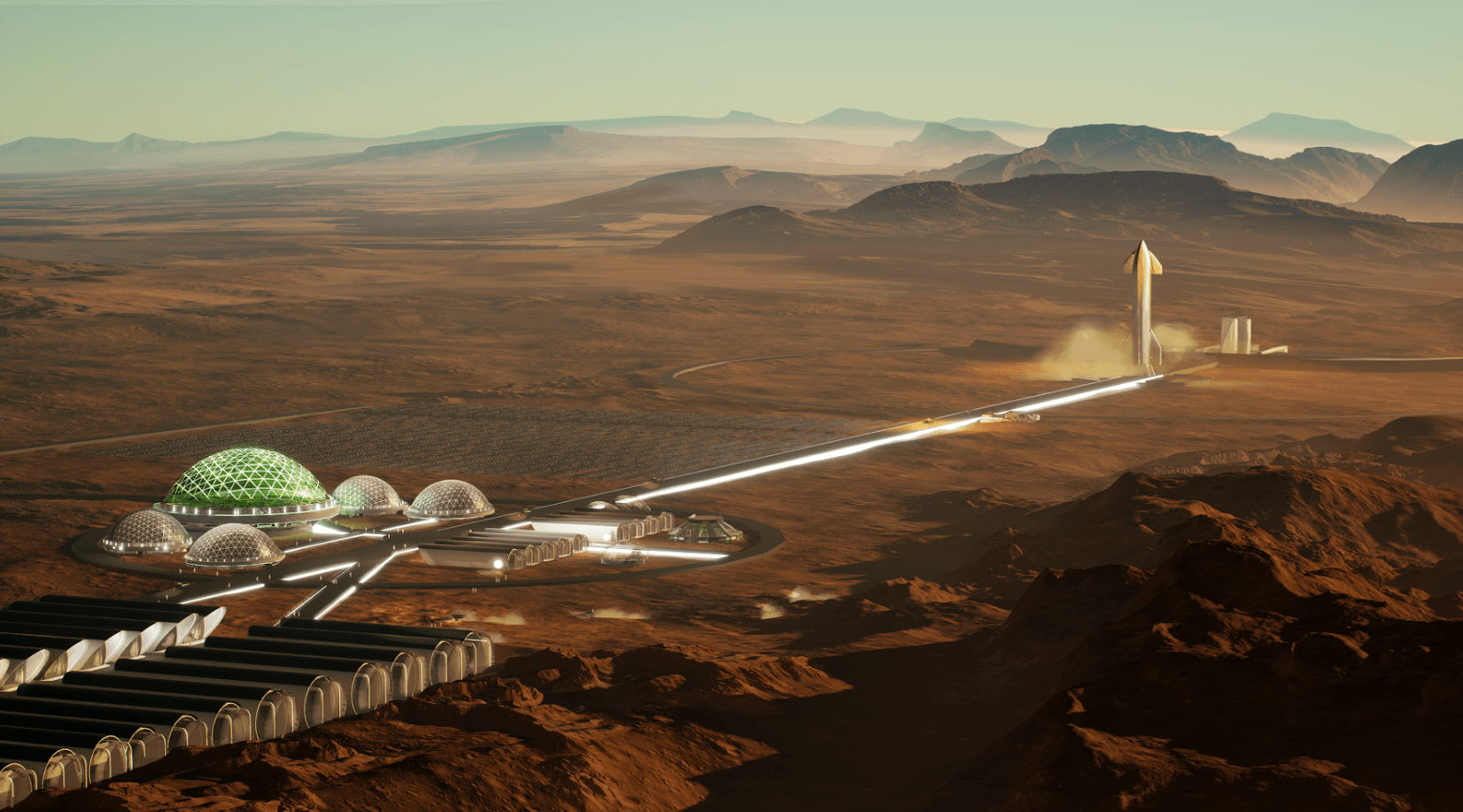

At Starbase on Thursday, April 4, SpaceX Chief Engineer Elon Musk provided an update on the company’s plans to send humanity to Mars, the best destination to begin making life multiplanetary.

All of SpaceX’s current programs, including Falcon, Dragon, Starlink, and Starship are integral to developing the technologies necessary to make missions to Mars a reality. The update included near-term priorities for Starship that will unlock its ability to be fully and rapidly reusable, the core enabler for transforming humanity’s ability to send large amounts of payload to orbit and beyond. With more flight tests, significant vehicle upgrades, and missions returning astronauts to the surface of the Moon with NASA’s Artemis Program all coming soon, excitement will continue to be guaranteed with Starship.

The talk also includes the mechanics and challenges of traveling to Mars, along with what we’re building today to enable sending around a million people and several million tonnes to the Martian surface in the years to come.

The second flight test of Starship and Super Heavy achieved a number of important milestones as we continue to advance the capabilities of the most powerful launch system ever developed.

On November 18, 2023, Starship successfully lifted off at 7:02 a.m. CT from Starbase in Texas. All 33 Raptor engines on the Super Heavy Booster started up successfully and, for the first time, completed a full-duration burn during ascent. Starship then executed a successful hot-stage separation, the first time this technique has been done successfully with a vehicle of this size.

Following stage separation, Super Heavy initiated its boostback burn, which sends commands to 13 of the vehicle’s 33 Raptor engines to propel the rocket toward its intended landing location. During this burn, several engines began shutting down before one engine failed energetically, quickly cascading to a rapid unscheduled disassembly (RUD) of the booster. The vehicle breakup occurred more than three and a half minutes into the flight at an altitude of ~90 km over the Gulf of Mexico.

The most likely root cause for the booster RUD was determined to be filter blockage where liquid oxygen is supplied to the engines, leading to a loss of inlet pressure in engine oxidizer turbopumps that eventually resulted in one engine failing in a way that resulted in loss of the vehicle. SpaceX has since implemented hardware changes inside future booster oxidizer tanks to improve propellant filtration capabilities and refined operations to increase reliability.

At vehicle separation, Starship’s upper stage successfully lit all six Raptor engines and flew a normal ascent until approximately seven minutes into the flight, when a planned vent of excess liquid oxygen propellant began. Additional propellant had been loaded on the spacecraft before launch in order to gather data representative of future payload deploy missions and needed to be disposed of prior to reentry to meet required propellant mass targets at splashdown.

A leak in the aft section of the spacecraft that developed when the liquid oxygen vent was initiated resulted in a combustion event and subsequent fires that led to a loss of communication between the spacecraft’s flight computers. This resulted in a commanded shut down of all six engines prior to completion of the ascent burn, followed by the Autonomous Flight Safety System detecting a mission rule violation and activating the flight termination system, leading to vehicle breakup. The flight test’s conclusion came when the spacecraft was as at an altitude of ~150 km and a velocity of ~24,000 km/h, becoming the first Starship to reach outer space.

SpaceX has implemented hardware changes on upcoming Starship vehicles to improve leak reduction, fire protection, and refined operations associated with the propellant vent to increase reliability. The previously planned move from a hydraulic steering system for the vehicle’s Raptor engines to an entirely electric system also removes potential sources of flammability.

The water-cooled flame deflector and other pad upgrades made after Starship’s first flight test performed as expected, requiring minimal post-launch work to be ready for vehicle tests and the next integrated flight test.

Following the flight test, SpaceX led the investigation efforts with oversight from the FAA and participation from NASA, and the National Transportation Safety Board.

Upgrades derived from the flight test will debut on the next Starship and Super Heavy vehicles to launch from Starbase on Flight 3. SpaceX is also implementing planned performance upgrades, including the debut of a new electronic Thrust Vector Control system for Starship’s upper stage Raptor engines and improving the speed of propellant loading operations prior to launch.

More Starships are ready to fly, putting flight hardware in a flight environment to learn as quickly as possible. Recursive improvement is essential as we work to build a fully reusable launch system capable of carrying satellites, payloads, crew, and cargo to a variety of orbits and Earth, lunar, or Martian landing sites.

The first flight test of a fully integrated Starship and Super Heavy was a critical step in advancing the capabilities of the most powerful launch system ever developed. Starship’s first flight test provided numerous lessons learned that are directly contributing to several upgrades being made to both the vehicle and ground infrastructure to improve the probability of success on future Starship flights. This rapid iterative development approach has been the basis for all of SpaceX’s major innovative advancements, including Falcon, Dragon, and Starlink. SpaceX has led the investigation efforts following the flight with oversight from the FAA and participation from NASA and the National Transportation Safety Board.

Starship and Super Heavy successfully lifted off for the first time on April 20, 2023 at 8:33 a.m. CT (13:33:09 UTC) from the orbital launch pad at Starbase in Texas. Starship climbed to a maximum altitude of ~39 km (24 mi) over the Gulf of Mexico. During ascent, the vehicle sustained fires from leaking propellant in the aft end of the Super Heavy booster, which eventually severed connection with the vehicle’s primary flight computer. This led to a loss of communications to the majority of booster engines and, ultimately, control of the vehicle. SpaceX has since implemented leak mitigations and improved testing on both engine and booster hardware. As an additional corrective action, SpaceX has significantly expanded Super Heavy’s pre-existing fire suppression system in order to mitigate against future engine bay fires.

The Autonomous Flight Safety System (AFSS) automatically issued a destruct command, which fired all detonators as expected, after the vehicle deviated from the expected trajectory, lost altitude and began to tumble. After an unexpected delay following AFSS activation, Starship ultimately broke up 237.474 seconds after engine ignition. SpaceX has enhanced and requalified the AFSS to improve system reliability.

SpaceX is also implementing a full suite of system performance upgrades unrelated to any issues observed during the first flight test. For example, SpaceX has built and tested a hot-stage separation system, in which Starship’s second stage engines will ignite to push the ship away from the booster. Additionally, SpaceX has engineered a new electronic Thrust Vector Control (TVC) system for Super Heavy Raptor engines. Using fully electric motors, the new system has fewer potential points of failure and is significantly more energy efficient than traditional hydraulic systems.

SpaceX also made significant upgrades to the orbital launch mount and pad system in order to prevent a recurrence of the pad foundation failure observed during the first flight test. These upgrades include significant reinforcements to the pad foundation and the addition of a flame deflector, which SpaceX has successfully tested multiple times.

Testing development flight hardware in a flight environment is what enables our teams to quickly learn and execute design changes and hardware upgrades to improve the probability of success in the future. We learned a tremendous amount about the vehicle and ground systems during Starship’s first flight test. Recursive improvement is essential as we work to build a fully reusable launch system capable of carrying satellites, payloads, crew, and cargo to a variety of orbits and Earth, lunar, or Martian landing sites.

Vast announced today that SpaceX will launch what is expected to be the world’s first commercial space station, known as Vast Haven-1, quickly followed by two human spaceflight missions to said space station. Scheduled to launch on a Falcon 9 rocket to low-Earth orbit no earlier than August 2025. Haven-1 will be a fully-functional independent space station and eventually be connected as a module to a larger Vast space station currently in development.

Upon launch of Haven-1, Falcon 9 will launch Vast’s first human spaceflight mission to the commercial space station, Vast-1. Dragon and its four-person crew will dock with Haven-1 for up to 30 days while orbiting Earth. Vast also secured an option for an additional human spaceflight mission to the station aboard a Dragon spacecraft.

The Vast-1 crew selection process is underway and the crew will be announced at a future date. Once finalized, SpaceX will provide crew training on Falcon 9 and the Dragon spacecraft, emergency preparedness, spacesuit and spacecraft ingress and egress exercises, as well as partial and full mission simulations including docking and undocking for return to Earth.

Vast’s long-term goal is to develop a 100-meter-long multi-module spinning artificial gravity space station launched by SpaceX’s Starship transportation system. In support of this, Vast will explore conducting the world’s first spinning artificial gravity experiment on a commercial space station with Haven-1.

This new partnership between Vast and SpaceX will continue to create and accelerate greater accessibility to space and more opportunities for exploration on the road to making humanity multiplanetary.

Japanese entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa announced today ten crewmembers, including two backups, who will join him on the dearMoon mission. The dearMoon crew will be the first humans Starship will launch, fly around the Moon, and safely return to Earth. Over the course of their weeklong journey, this crew of artists, content creators, and athletes from all around the world will also travel within 200 km of the lunar surface.

More than one million people in 249 countries and regions around the world applied to fly on Starship as part of the dearMoon mission. This flight is an important step toward enabling access for people who dream of traveling to space. In sharing their experiences flying around the Moon, this crew will inspire everyone back home on Earth, and we look forward to flying them.

Sustaining long-term human exploration on the Moon will require the safe and affordable transportation of crew and significant amounts of cargo.

NASA announced it has modified its contract with SpaceX to further develop the Starship human landing system. Initially selected to develop a lunar lander capable of carrying astronauts between lunar orbit and the surface of the Moon as part of NASA’s Artemis III mission—marking humanity's first return to the Moon since the Apollo program’s final mission in 1972—SpaceX will now support a second human landing demonstration as part of NASA's Artemis IV mission. Additionally, SpaceX will demonstrate Starship’s capability to dock with Gateway, a small space station that will orbit the Moon in efforts to support both lunar and deep-space exploration, accommodate four crew members, and deliver more supplies, equipment, and science payloads that are needed for extensive surface exploration.

SpaceX’s Starship spacecraft and Super Heavy rocket represent an integrated and fully reusable launch, propellant delivery, rendezvous, and planetary lander system with robust capabilities and safety features uniquely designed to deliver these essential building blocks. We are honored to be a part of NASA’s Artemis Program to help return humanity to the Moon and usher in a new era of human space exploration.

Dennis and Akiko Tito are the first two crewmembers announced on Starship’s second commercial spaceflight around the Moon. This will be Dennis’ second mission to space after becoming the first commercial astronaut to visit the International Space Station in 2001, and Akiko will be among the first women to fly around the Moon on a Starship. The Titos joined the mission to contribute to SpaceX’s long-term goal to advance human spaceflight and help make life multiplanetary.

Over the course of a week, Starship and the crew will travel to the Moon, fly within 200 km of the Moon’s surface, and complete a full journey around the Moon before safely returning to Earth. This mission is expected to launch after the Polaris Program’s first flight of Starship and dearMoon.

SpaceX’s Chief Engineer Elon Musk and T-Mobile’s CEO and President Mike Sievert announced today a breakthrough plan to provide truly universal cellular connectivity.

Despite powerful LTE and 5G terrestrial wireless networks, more than 20% of the United States land area and 90% of the Earth remain uncovered by wireless companies. These dead zones have serious consequences for remote communities and those who travel off the grid for work or leisure. The telecom industry has struggled to cover these areas with traditional cellular technology due to land-use restrictions (e.g. National Parks), terrain limits (e.g. mountains, deserts and other topographical realities) and the globe’s sheer vastness. In those areas, people are either left disconnected or resort to lugging around a satellite phone and paying exorbitant rates.

Leveraging Starlink, SpaceX’s constellation of satellites in low Earth orbit, and T-Mobile’s wireless network, the companies are planning to provide customers text coverage practically everywhere in the continental US, Hawaii, parts of Alaska, Puerto Rico and territorial waters, even outside the signal of T-Mobile’s network. The service will be offered starting with a beta in select areas by the end of next year after SpaceX’s planned satellite launches. Text messaging, including SMS, MMS, and participating messaging apps, will empower customers to stay connected and share experiences nearly everywhere. Afterwards, the companies plan to pursue the addition of voice and data coverage.

In addition, Elon and Mike shared their vision for expanding Coverage Above and Beyond globally, issuing an open invitation to the world’s carriers to collaborate for truly global connectivity. T-Mobile committed to offer reciprocal roaming to those providers working with them to enable this vision.

This service will have a tremendous impact on the safety, peace of mind, and individual and business opportunities around the globe. The applications range from connecting hikers in national parks, rural communities, remote sensors and devices, and people and devices in emergency situations, such as firefighters.

This satellite-to-cellular service will provide nearly complete coverage anywhere a customer can see the sky—meaning you can continue texting and eventually make a cell phone call even when you leave terrestrial coverage. We’ve designed our system so that no modifications are required to the cell phone everyone has in their pocket today, and no new firmware, software updates, or apps are needed. As a complementary technology to terrestrial networks, SpaceX can enable mobile network operators to connect more people, fulfill coverage requirements, and create new business opportunities.

If you represent a mobile network operator or regulatory agency and are interested in partnering with SpaceX to bring this new level of mobile connectivity to your region, please reach out to us at direct2cell@spacex.com.

SpaceX was founded to revolutionize space technology towards making life multiplanetary. SpaceX is the world’s leading provider of launch services and is proud to be the first private company to have delivered astronauts to and from the International Space Station (ISS), and the first and only company to complete an all-civilian crewed mission to orbit. As such, SpaceX is deeply committed to maintaining a safe orbital environment, protecting human spaceflight, and ensuring the environment is kept sustainable for future missions to Earth orbit and beyond.

SpaceX has demonstrated this commitment to space safety through action, investing significant resources to ensure that all our launch vehicles, spacecraft, and satellites meet or exceed space safety regulations and best practices, including:

-

Designing and building highly reliable, maneuverable satellites that have demonstrated reliability of greater than 99%

-

Operating at low altitudes (below 600 km) to ensure no persistent debris, even in the unlikely event a satellite fails on orbit

-

Inserting satellites at an especially low altitude to verify health prior to raising into their on-station/operational orbit

-

Transparently sharing orbital information with other satellite owners/operators

-

Developed an advanced collision avoidance system to take effective action when encounter risks exceed safe thresholds

With space sustainability in mind, we have pushed the state-of-the-art in key technology areas like flying satellites at challenging low altitudes, the use of sustainable electric propulsion for maneuvering and active de-orbit, and employing inter-satellite optical communications to constantly maintain contact with satellites. SpaceX is striving to be the world’s most open and transparent satellite operator, and we encourage other operators to join us in sharing orbital data and keeping the public and governments updated with detailed information about operations and practices.

SpaceX continues to innovate to accelerate space technologies, and we are currently providing much-needed internet connectivity to people all over the globe, including underserved and remote parts of the world, with our Starlink constellation. Below are our operating principles demonstrating our commitment to space sustainability and safety.

Designing and Building Safe, Reliable and Demisable Satellites

SpaceX satellites are designed and built for high reliability and redundancy in both supply chain and satellite design to successfully carry out their five-year design life. Rigorous part and system-level screening and testing enable us to reliably build and launch satellites at very high rates. We have the capacity to build up to 45 satellites per week, and we have launched up to 240 satellites in a single month. This is an unprecedented rate of deployment for a complex space system — and reflects SpaceX’s commitment to increase broadband accessibility around the world with Starlink as soon as feasible.

The reliability of the satellite network is currently higher than 99% following the deployment of over 2,000 satellites, where only 1% have failed after orbit raising. We de-orbit satellites that are at risk of becoming non-maneuverable to prevent dead satellites from accumulating in orbit. Although this comes at the cost of losing otherwise healthy satellites, we believe this proactive approach is the right thing for space sustainability and safety.

Our satellites use multiple strategies to prevent debris generation in space: design for demise, controlled deorbit to low altitudes, low orbit insertion, low operating orbit, on-board collision avoidance system, reducing the chance small debris will damage the satellite with a low profile satellite chassis and using Whipple shields to protect the key components, reducing risk of explosion with extensive battery pack protection, and failure modes that do not create secondary debris.

SpaceX satellites are propulsively deorbited within weeks of their end-of-mission-life. We reserve enough propellant to deorbit from our operational altitude, and it takes roughly 4 weeks to deorbit. Once the satellites reach an appropriate altitude, we coordinate with the 18th Space Control Squadron. Once coordinated, we initiate a high drag mode, causing the satellite’s velocity to reduce sufficiently that the satellite deorbits. The satellites deorbit quickly from this altitude, depending on atmospheric density. SpaceX is the only commercial operator to have developed expertise in flying in a controlled way in this low altitude, high drag environment, which is incredibly difficult and required a significant investment in specialized satellite engineering. SpaceX made these investments so that we can maintain controlled flight as long as possible prior to deorbit, providing us with the ability to perform any necessary maneuvers to further reduce collision risk.

When a satellite’s altitude decays, it encounters a constantly increasing atmospheric density. Initially, these molecules impact the satellite, but as the air density increases, a high-pressure shock wave forms in front of the spacecraft. As the satellite slows down and descends into the atmosphere, its orbital energy is transferred into the air, heating it to a plasma. The hot plasma sheath envelops the satellite, causing intense heating. Starlink satellites are designed to demise as they reenter the Earth’s atmosphere, meaning they pose no risk to people or property on the ground. Design for demise required the investment of significant engineering resources and often required adding cost and even mass to our satellites, such as our decision to use aluminum rather than composite overwrap pressure vessels for the fuel tank for our propulsion system. SpaceX has safely deorbited over 200 satellites utilizing this approach. By building reliable, debris minimizing satellites, planning for active deorbit and designing for full demisability, we ensure we’re keeping space sustainable and safe.

Extremely Low Orbit Insertion

In addition to SpaceX designing and building very reliable satellites, we further mitigate risks by deploying the satellites into extremely low orbits relative to industry standards. We deploy our satellites into low altitudes (<350km) and use our state-of-the-art electric propulsion thruster to boost the satellites to the operational altitude of approximately 550 km to start their mission. We leverage SpaceX’s technical advancements to maintain controlled flight at these low altitudes. By deploying the satellites into such low altitudes, in the rare case where any SpaceX satellite does not pass initial system checkouts, it is quickly and actively deorbited using its thruster or passively by atmospheric drag. This approach is not without complexity or other challenges. This was best evidenced by the recent February 3rd Starlink launch, after which increased drag from a geomagnetic storm resulted in the premature deorbit of 38 satellites. Despite such challenges, SpaceX firmly believes that a low insertion altitude is key for ensuring responsible space operations.

Operating Below 600 km

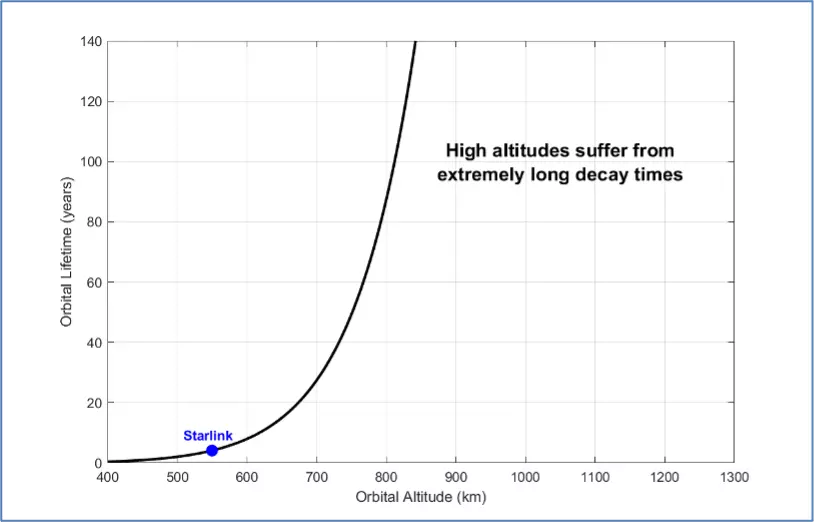

SpaceX operates its satellites at an altitude below 600 km because of the reduced natural orbit decay time relative to those above 600 km. Starlink operates in \"self-cleaning\" orbits, meaning that non-maneuverable satellites and debris will lose altitude and deorbit due to atmospheric drag within 5 to 6 years, and often sooner, see Fig. 1. This greatly reduces the risk of persistent orbital debris, and vastly exceeds the FCC and international standard of 25 years (which we believe is outdated and should be reduced). Natural deorbit from altitudes higher than 600 km poses significantly higher orbital debris risk for many years at all lower orbital altitudes as the satellite or debris deorbits. Several other commercial satellite constellations are designed to operate above 1,000 km, where it requires hundreds of years for spacecraft to naturally deorbit if they fail prior to deorbit or are not deorbited by active debris removal, as in Fig. 1. SpaceX invested considerable effort and expense in developing satellites that would fly at these lower altitudes, including investment in sophisticated attitude and propulsion systems. SpaceX is hopeful active debris removal technology will be developed in the near term, but this technology does not currently exist.

Fig. 1: Orbital lifetime for a satellite with a mass-to-area ratio of 40kg/m2 at various starting altitudes and average solar cycle.

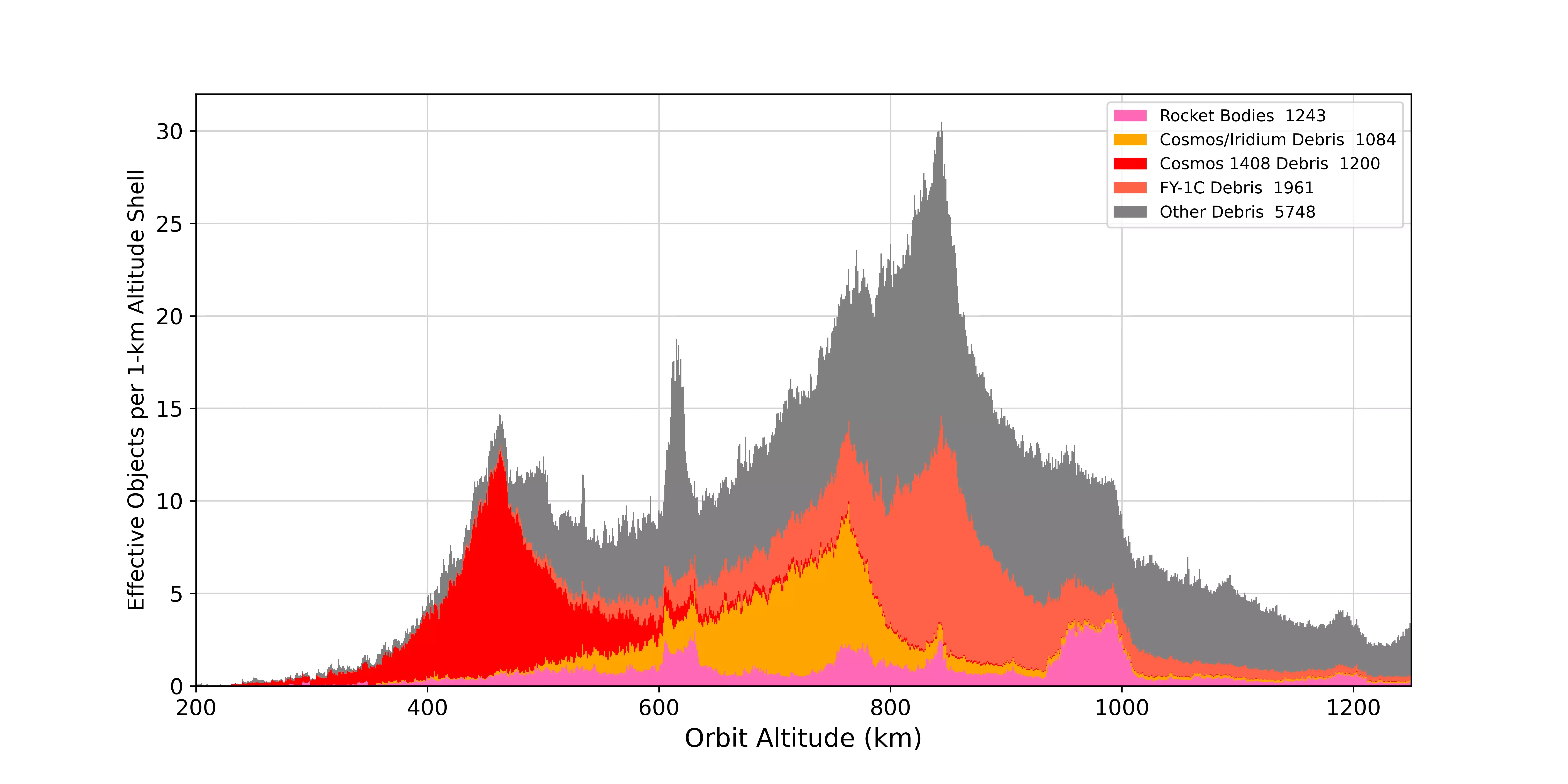

Fig. 2 shows debris as a function of each altitude. The debris generated from collision events from satellites flying at altitudes above 600km will stay in orbit for decades to come and create orbital debris risk for each altitude they pass through as they deorbit.

Fig. 2: Debris per 1-km altitude shell as a function of orbital altitude.

Transparency and Data Sharing

SpaceX transparently and continuously shares the details of our Starlink network both with governments and other satellite owners/operators. We work to ensure accurate, relevant, and up-to-date information related to space safety, and space situational awareness is shared with all operators. SpaceX shares high fidelity future position and velocity prediction data (ephemerides) for all SpaceX satellites.

SpaceX shares both propagated ephemerides and covariance (statistical uncertainty of the predictions) data on Space-Track.org and encourages all other operators to do so, as this enables more meaningful and accurate computation of collision risks. SpaceX is also working to make it even easier for anyone to access our ephemerides by eliminating any requirement to login to Space-Track.org to see our data.

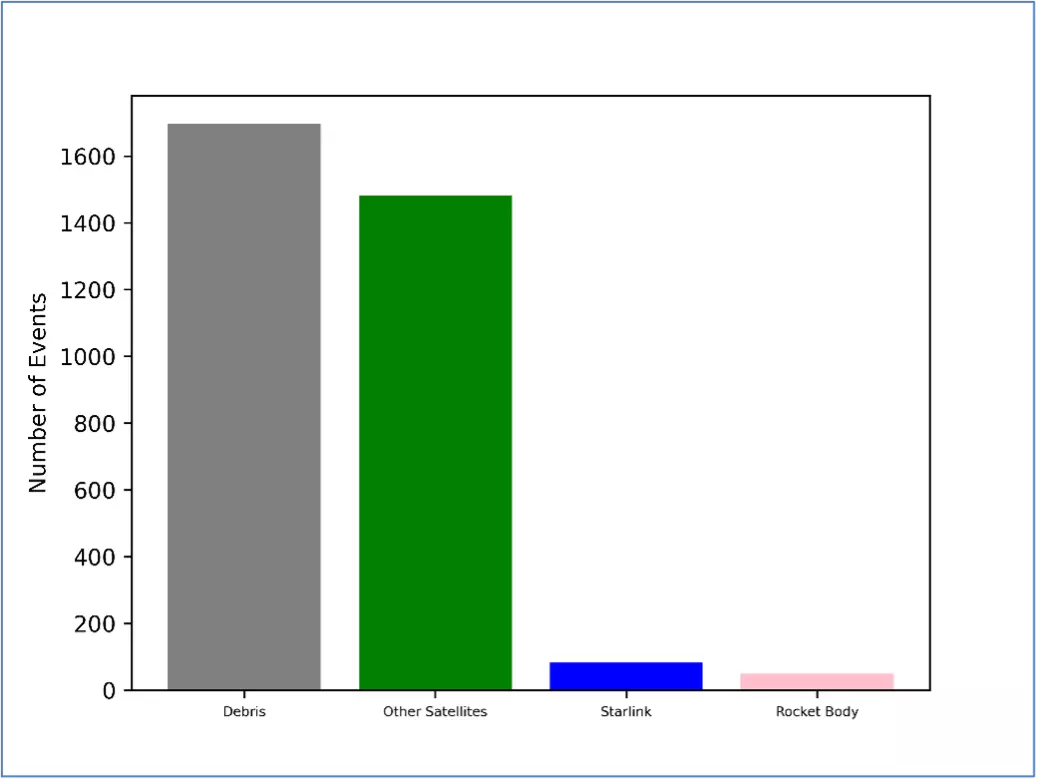

In addition to providing our satellite ephemerides, SpaceX volunteered to provide routine system health reports to the Federal Communications Commission ("FCC"), something no other operator has ever offered or currently does. These reports indicate the status of our constellation, including a summary of the operational status of our satellite fleet, and the number of maneuvers performed to reduce the collision probability with other objects. Fig. 3 is a sample of the number of maneuvers Starlink has done over the 6-month period from June 2021 through November 2021.

Fig. 3: Number of SpaceX maneuvers from July-Dec 2021 (total was 3300)

Collision Avoidance System

SpaceX has high fidelity location and prediction data for our satellites from deployment through end-of-life disposal, and we share this information continuously with the U.S. Space Force, LeoLabs and other operators for tracking and collision avoidance screening. SpaceX satellites regularly downlink accurate orbital information from onboard GPS. We use this orbital information, combined with planned maneuvers, to accurately predict future ephemerides, which are uploaded to Space-Track.org three times per day. LeoLabs downloads our ephemerides from Space-Track.org and along with the U.S. Space Force's 18th Space Control Squadron screens these trajectories against other satellites and debris to predict any potential conjunctions. Such conjunctions are communicated back to SpaceX and other satellite owners/operators as Conjunction Data Messages (CDMs), which include satellite state vectors, position uncertainties, maneuverability status, and the owner/operator information. SpaceX uploads these CDMs to applicable SpaceX satellites.

To accomplish safe space operations in a scalable way, SpaceX has developed and equipped every SpaceX satellite with an onboard, autonomous collision avoidance system that ensures it can maneuver to avoid potential collisions with other objects. If there is a greater than 1/100,000 probability of collision (10x lower than the industry standard of 1/10,000) for a conjunction, satellites will plan avoidance maneuvers. When planning a maneuver for any conjunction, the satellites take care to avoid inadvertently increasing risk for other conjunctions above the same threshold.

By default, Starlink satellites assume maneuver responsibility for all conjunction events. Upon receipt of a high-probability conjunction with another maneuverable satellite, SpaceX coordinates with the other operator. SpaceX operators are on-call 24/7 to coordinate and respond to inquiries from other operators; contact information for high-urgency requests is available to other operators via Space-Track.org. If the other operator prefers to take maneuver responsibility themselves, Starlink satellites can be commanded to not maneuver for an event.

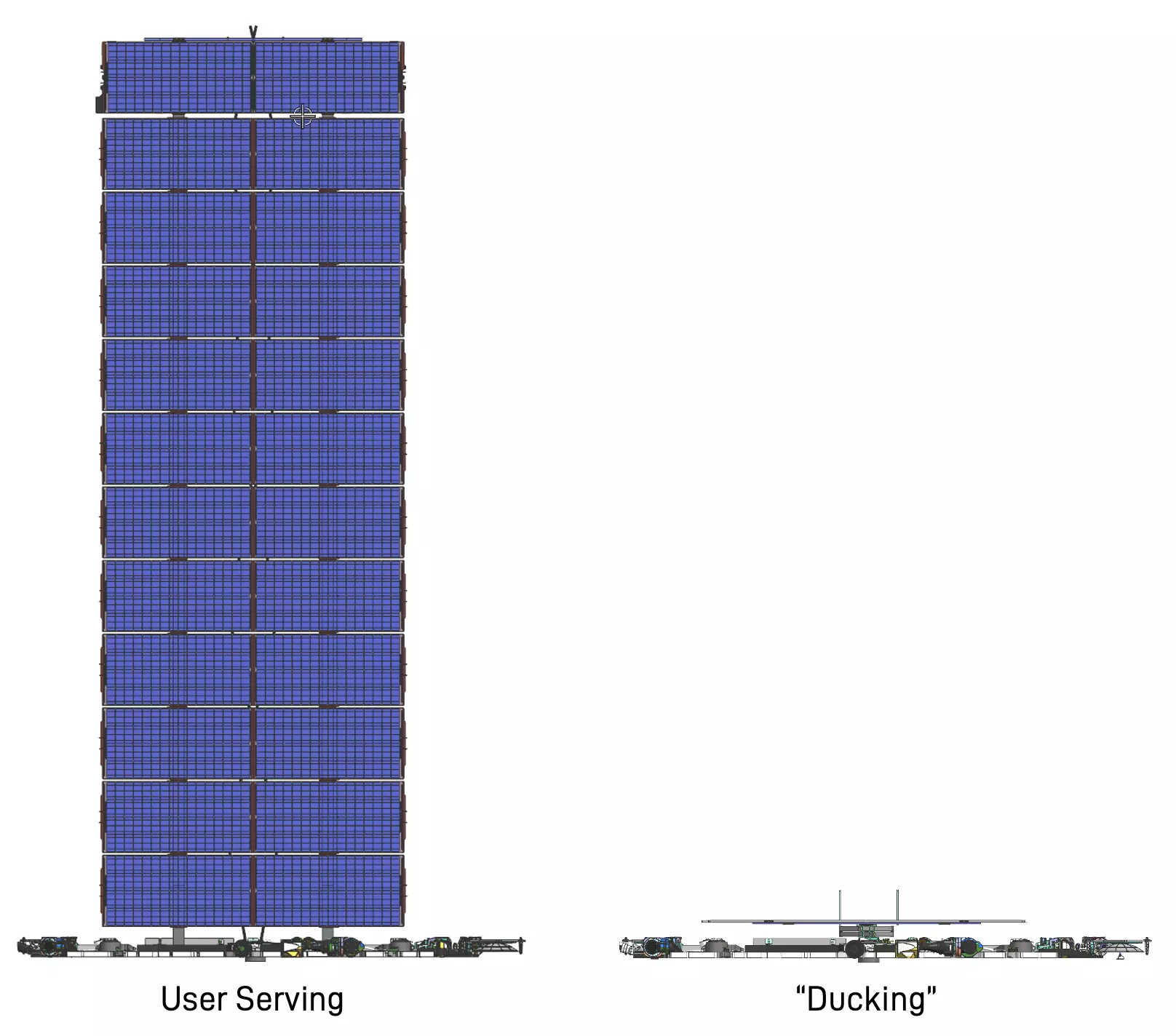

In addition to collision avoidance maneuvers, Starlink satellites can autonomously “duck” for conjunctions, orienting their attitude to have the smallest possible cross-section (like the edge of a sheet of paper) in the direction of the potential conjunction, reducing collision probability by another 4-10x (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: SpaceX’s “duck” maneuver (right) minimizing area in potential collision direction (out of page) compared with worst-case orientation (left)

SpaceX’s collision avoidance system has been thoroughly reviewed by NASA’s Conjunction Assessment and Risk Analysis (CARA) program under a Space Act Agreement (SAA) with NASA, and per the SAA, NASA relies on it to avoid collisions with NASA science spacecraft.

SpaceX satellites’ flight paths are designed to avoid inhabited space stations like the International Space Station (ISS) and the Chinese Space Station Tiangong by a wide margin. We work directly with NASA and receive ISS maneuver plans to stay clear of their current and planned trajectory including burns. China does not publish planned maneuvers, but we still make every effort to avoid their station with ISS-equivalent clearance based on publicly available ephemerides.

SpaceX is proud of our sophisticated and constantly improving design, test, and operational approach to improve space sustainability and safety, which are critical towards accelerating space exploration while bringing Internet connectivity to the globe. We urge all satellite owner/operators to make similar investments in sustainability and safety and make their operations transparent. We encourage all owner/operators to generate high quality propagated ephemeris and covariance for screening by the 18th Space Control Squadron and to openly share this information with others to maximize coordination to ensure a sustainable and safe space environment for the future. Ultimately, space sustainability is a technical challenge that can be effectively managed with the appropriate assessment of risk, the exchange of information, and the proper implementation of technology and operational controls. Together we can ensure that space is available for humanity to use and explore for generations to come.

Jared Isaacman, founder and CEO of Shift4 who commanded the Inspiration4 mission, announced today the Polaris Program, a first-of-its-kind effort to rapidly advance human spaceflight capabilities, while continuing to raise funds and awareness for important causes here on Earth. The program will consist of up to three human spaceflight missions that will demonstrate new technologies, conduct extensive research, and ultimately culminate in the first flight of SpaceX’s Starship with humans on board.